Alnylam Pharmaceuticals is responsible for the funding and content of this website. The site is intended for Healthcare Professionals in Europe, Middle East and Africa. For disease awareness purposes only.

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals is responsible for the funding and content of this website. The site is intended for Healthcare Professionals in Europe, Middle East and Africa. For disease awareness purposes only.

WHAT MORE MAY BE

Recurrent kidney stones in an adult or any kidney stone in a child may be early signs of a metabolic stone disease with potentially devastating consequences, such as primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1).1–4

Any stone or a family history of stones may be red flags.1,3–5

Recurrent and/or unusual stones* may be red flags.1,6–9

A 24-hour urine test can be used to help detect metabolic stone disease.10–12

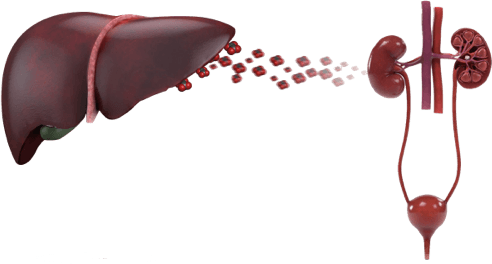

PH1 is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in the AGXT gene, leading to overproduction of oxalate in the liver.3,4 Over time, oxalate overproduction can lead to progressive kidney function decline.2,4

of PH1 patients may be undiagnosed, although data on prevalence are limited.17

is the median delay in adults between onset of clinical manifestations and diagnosis.15

of diagnoses in adults occur after progression to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).14,18–21

Current management approaches to PH1 aim at enhancing clearance of oxalate, inhibiting oxalate crystallisation, or lowering oxalate production by the liver.3,4,11

See how genetic testing plays an important role in a PH1 diagnosis.3,11

References: 1. Ferraro PM, D’Addessi A, Gambaro G. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(4):811–820. 2. Hoppe B. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(8):467–475. 3. Milliner DS, Harris PC, Sas DJ, et al. Primary hyperoxaluria type 1. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Updated 15 August 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1283/ 4. Cochat P, Rumsby G. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):649–658. 5. Hoppe B, Kemper MJ. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(3):403–413. 6. Jendeberg J, Geijer H, Alshamari M, et al. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(11):4775–4785. 7. Carrasco A Jr, Granberg CF, Gettman MT, et al. Urology. 2015;85(3):522–526. 8. Hoppe B, Beck BB, Milliner DS. Kidney Int. 2009;75(12):1264–1271. 9. Leumann E, Hoppe B. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(9):1986–1993. 10. Ben-Shalom E, Frishberg Y. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(10):1781–1791. 11. Cochat P, Hulton SA, Acquaviva C, et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(5):1729–1736. 12. Groothoff JW, Metry E, Deesker L, et al. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(3):194–211. 13. Mandrile G, Rumsby G, Sciannameo V, et al. Clin Kidney J. 2025;18(7):sfaf194. 14. Harambat J, Fargue S, Acquaviva C, et al. Kidney Int. 2010;77(5):443–449. 15. van der Hoeven SM, van Woerden CS, Groothoff JW. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3855–3862. 16. Hulton SA. Int J Surg. 2016;36(Pt D):649–654. 17. Hopp K, Cogal AG, Bergstralh EJ, et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(10):2559–2570. 18. van Woerden CS, Groothoff JW, Wanders RJA, et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(2):273–279. 19. Mandrile G, van Woerden CS, Berchialla P, et al; for OxalEurope Consortium. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1197–1204. 20. Lieske JC, Monico CG, Holmes WS, et al. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25(3):290–296. 21. Soliman NA, Nabhan MM, Abdelrahman SM, et al. Nephrol Ther. 2017;13(3):176–182.

PH1-INTR-00035 | January 2026

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals is responsible for the funding and content of this website. The site is intended for Healthcare Professionals in Europe, Middle East and Africa. For disease awareness purposes only.

By accessing the website, you confirm to be a Healthcare Professional from Europe, Middle East, or Africa:

If you are not a Healthcare Professional, please access the LivingwithPH1.eu website here.